Catholicism in the new world

Discover More:

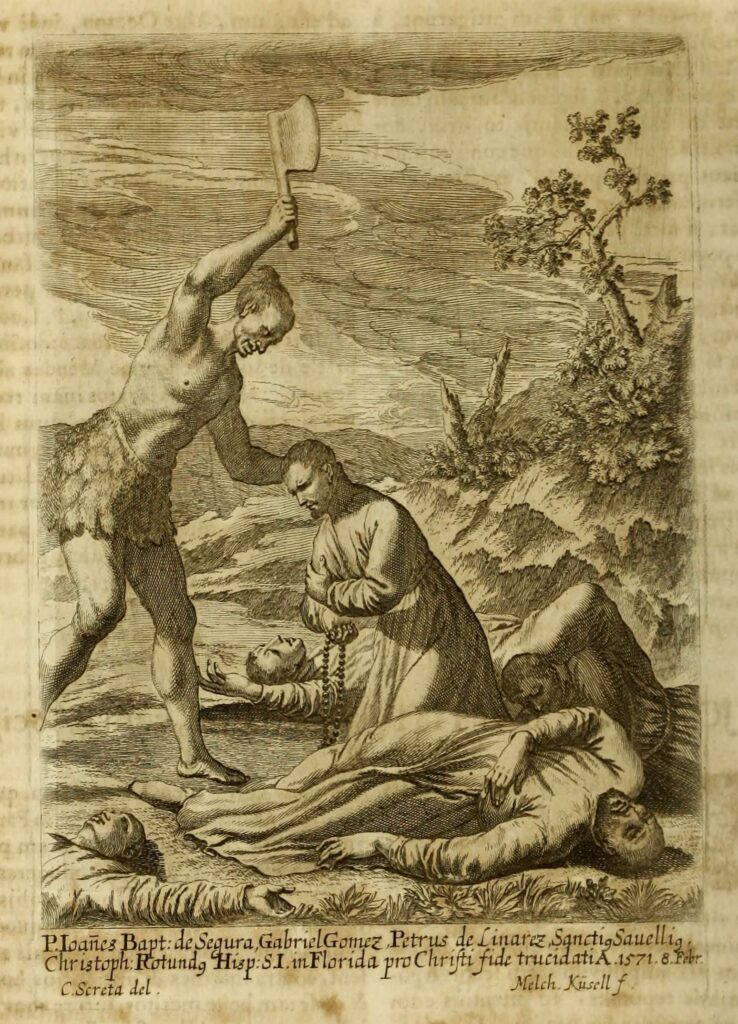

Thirty-seven years before the English settlement at Jamestown, a group of Spanish Jesuits came to Virginia to found a mission in the New World. In 1570, Father Juan Baptiste de Segura was accompanied by seven other Jesuit priests and brothers, and one young altar boy. Traveling with them as their guide was the son of an Algonquian chief, Paquiquineo.

Paquiquineo had first encountered settlers from the New World nearly a decade before, when a group of Europeans arrived in the Bahía de Madre de Dios (“Bay of the Mother of God”), today known as the Chesapeake Bay, in 1560. Paquiquineo’s tribe lived in an area called Ajacán, in modern-day Virginia. He was taken by the settlers back to Europe, where he lived at the Spanish royal court as a guest to King Philip II. While there, the young Algonquian learned to speak Spanish and was introduced to Spanish life and culture; most importantly, it was there that he learned about the Christian religion for the first time. Eventually, after several years of living among the Spanish, Paquiquineo decided to convert to Catholicism: he was baptized into the Church and received the name Luis. Those around him called him Don Luis, out of respect for his noble status among the Algonquian tribe.

After his baptism, Don Luis received the other sacraments of initiation with the assistance of a relatively new religious order at the time, the Society of Jesus. His connections with the Jesuit order in Spain brought Don Luis to the attention of Father Juan Baptiste de Segura, a Jesuit priest who was working to establish a mission in Ajacán. Father Segura asked Don Luis to join their mission: in this way, Don Luis could return to his home, and he could act as their guide. Moreover, he could join their missionary efforts in bringing to the Algonquins the Gospel that he himself had come to embrace.

Thus, the group departed for the new world: Don Luis was accompanied by two priests, Father Juan Baptista de Segura, S.J. and Father Luis de Quiros, S.J.; three brothers, Brother Gabriel Gomez, S.J., Brother Sancho Zeballos, S.J. and Brother Pedro Linares, S.J.; and three volunteers who later entered the novitiate, Gabriel de Solis, S.J., Juan Baptista Mendez, S.J. and Cristobal Redondo, S.J. Also joining the group was a young 14- or 15-year old boy, Alonso de Olmos, who had begged to join the mission and who traveled with them as their altar boy.

With Don Luis as their guide, the group managed to locate the part of modern-day Virginia where Don Luis’ village was situated. The missionaries quickly set to work and constructed a small settlement. Not long after their arrival, however, and much to the shock of Father Segura and the others, one day Don Luis abandoned the mission, renounced his faith, returned to his village and took several wives. The Jesuit fathers and brothers visited the village and begged Don Luis to stay true to his baptismal promises. Don Luis refused, but the Spanish missionaries returned to the village several more times, attempting to bring Don Luis back to the faith. On the last of these attempts, Don Luis sent a war party to kill the Jesuit messengers. Five days later, Don Luis led another war party to attack the settlement and kill the remaining Jesuit missionaries. All but the altar boy, Alonso de Olmos, were killed in the attacks.

Today, the Jesuit martyrs are commemorated with a plaque posted along the Colonial Parkway, in Williamsburg. Their cause for canonization has been joined with the Martyrs of La Florida.

To learn more about the Virginia Martyrs, listen to this lecture given by Father Andrew Fisher, available on the Basilica of Saint Mary Podcast.

In 1534, the English Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, recognizing King Henry VIII as head of the Church of England. In doing so, the English monarch indefinitely severed ties with the Catholic Church. The result was a centuries-long period of persecution and discrimination against Catholicism.

In the immediate aftermath of King Henry VIII’s split with Rome, Catholic men and women were thrown into confusion. England had been a deeply Catholic country, with a rich patrimony of saints, devout kings, cathedrals, monasteries, religious art and pious practices. However, the Act of Supremacy required believers to choose between loyalty to their king and loyalty to the Church. All government and Church officials were required to take the Oath of Supremacy, or else be guilty of treason – a fate that was famously suffered by Sir Thomas More. Monasteries who did not support the Act of Supremacy, or who did not meet the standards for a reformed religious life according to the king and his viceregent, Thomas Cromwell, were dissolved and their property seized. Some of these monks and nuns, such as the Carthusian monks of London, suffered martyrdom.

Unlike the Protestant revolts that were concurrently underway in other countries such as Germany, France and Switzerland, the English “protest” of the Catholic Church followed a more top-down approach. Anti-Catholic reforms were imposed by authority figures, and many English men and women were intially suspicious of a separation from the Church. However, the tide of popular opinion shifted decidedly against the Catholic Church under the reign of Henry VIII’s daughter, Queen Mary.

Queen Mary I, who was the daughter of Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, remained a devoted Catholic even during her father’s reforms. When she took the throne in 1553, she attempted to reverse many of the anti-Catholic measures that had been put in place by her father and during the brief reign of her half-brother, Edward VI. She put hundreds of Protestant faithful to death; many of them were burnt at the stake. This earned her the title “Bloody Mary” and led to a widespread distrust of the Catholic Church among the English people. Moreover, her unpopular marriage to Prince Philip II of Spain fueled existing geopolitical tensions and cemented the notion that Catholicism was linked with foreign powers. In the minds of 16th-century Englishmen, to be English was to be Anglican.

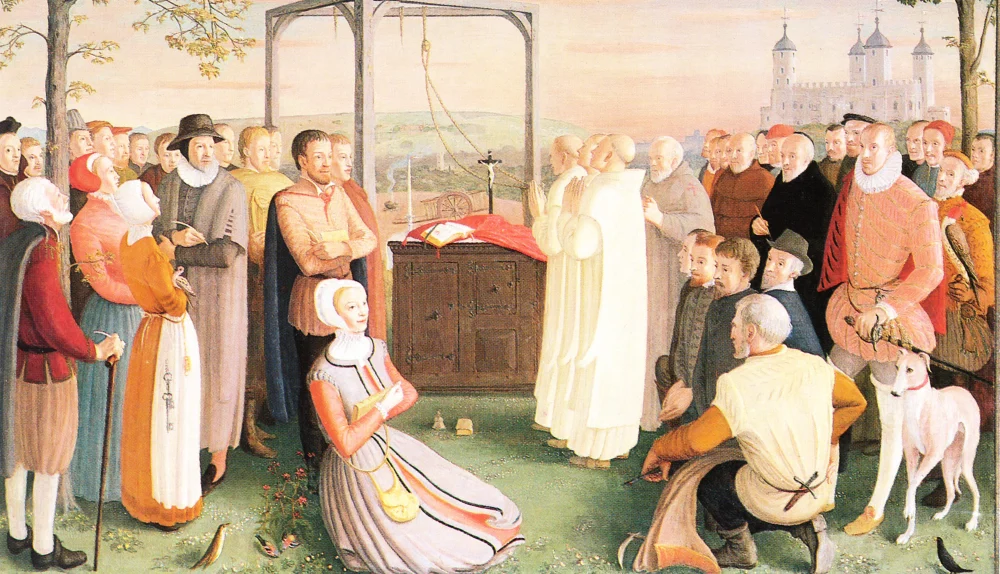

This mindset, now in all strata of English society, provided fertile ground for the harsh anti-Catholic penal laws enforced under Mary’s successor, Queen Elizabeth I. Her reign bore witness to countless martyrdoms, some 380 of which are officially recognized by the Catholic Church today, as well as political maneuvers that made the practice of Catholicism effectively impossible. Under Elizabeth, attendance at Anglican services was mandatory, and failure to do so resulted in heavy fines, seizure of property and imprisonment. Catholic priests caught ministering were imprisoned, tortured, executed or expelled; any person caught harboring a priest was subject to the death penalty. Catholics could not hold civic office, attend university or hold a passport (yes, passports existed in Tudor England!). Over the course of the succeeding decades, tensions between Catholics and Protestants would continue to wax and wane.

This was the backdrop for the earliest Catholic pilgrims to the English-speaking colonies. Exactly one century after Parliament enacted the Act of Supremacy, a group of Catholic pilgrims aboard the Ark and the Dove arrived in the New World, eager to start a new life in which they would be free to practice their religion.

Sir George Calvert was born in 1580 to a Catholic family. He was raised Catholic, although he later renounced the faith and took the Oath of Supremacy in order to attend Oxford University and enter political life. He was even involved in a 1613 commission to address Catholic grievances in Ireland; as part of the commission Calvert recommended more strictly enforcing conformity to the Church of England by suppressing Catholic schools and punishing priests.

Calvert was very successful as a politician. He gained the trust and admiration of King James I, who made Calvert Privy Councillor, secretary of state and Lord High Treasurer. In 1623, James I awarded Calvert with a large estate and tract of land in southeastern Ireland. His new seat, called Baltimore after the Irish name Baile an Tí Mhóir (“town of the big house”), earned him the title Lord Baltimore.

In late 1624, George Calvert resigned as secretary of state and converted back to Catholicism. His conversion obliged him to partially withdraw from political life, but he remained in King James I’s good favor as an advisor. However, when the king died in 1625 and was succeeded by his son, Charles I, George Calvert was removed from the Privy Council.

Calvert began to focus his attention on the New World. He had long been interested in the colonies for financial reasons, but his reversion to Catholicism led him to appreciate life in the colonies as an opportunity for freedom of worship. Thus, after years of petitioning the king, an initial land charter in Newfoundland, and a failed attempt at obtaining land in Virginia, George Calvert received a grant to establish the colony that would come to be known as Maryland.

Sadly, George Calvert died two months before negotiations for the colony were fully completed. However, his sons, Cecil and Leonard Calvert, took over the project. On March 25, 1634, the Feast of the Annunciation, Leonard Calvert arrived at the eastern shore of the lower Potomac River aboard the Ark and the Dove ships, along with over one hundred settlers. They named the first landing site Saint Clement’s Island, after Pope Clement I, and the mainland city, Saint Mary’s City, after the Blessed Mother. The colony was named Maryland, after Queen Henrietta Marie, Charles I’s French Catholic wife.

The voyagers accompanying Leonard Calvert on the Ark and the Dove were a diverse group. The majority were Protestant, although there were a number of Catholics, including three Jesuit priests. Some of the travelers were from wealthy families, seeking either adventure or a place to practice their faith, and others were poor, seeking their own land and a better life. Among the group was Thomas Greene, who became Maryland’s second governor, and Anne Cox, a widow who, according to unproven tradition, was a member of the Gerard family, prominent recusant Catholics. Greene and Cox were married by one of the accompanying Jesuit priests, Father Andrew White, and their marriage was the first Catholic wedding in the British American colonies. Their descendants were among the founding members of Saint Mary in Alexandria.

Sir Richard Brent (1573-1652) was an English lord from Gloucestershire, in western England. He and his wife, Elizabeth, had thirteen children: six boys and seven girls. The entire family was devout in its Catholic faith; according to historian Bruce E. Steiner, Sir Richard and the whole Brent family converted to Catholicism after his daughter, Catherine, decided to convert (Steiner, B. E. (1962). The Catholic Brents of Colonial Virginia: An Instance of Practical Toleration. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 70(4), 387–409). Catherine would later go on to enter the Monastery of Our Lady of Consolation, a Benedictine monastery that was established in Cambrai, France for English expatriates, since Englishwomen could not enter religious life under the Elizabethan anti-Catholic penal laws. Three of Catherine’s sisters also became nuns.

Sir Richard and his children suffered from the anti-Catholic persecution in England. Public records note several instances of their refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy. As a result, more than two-thirds of the family’s land and property were sequestered and they were imposed with heavy fines, “all of them being known papists” (The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. (1906). United States: Virginia Historical Society).

Four of the Brent children – Fulke, Giles, Margaret and Mary – chose to emigrate to the New World, to settle in the Maryland Colony that had recently been established by their cousin, Lord Calvert. They arrived in the late 1630s, just a few years after the first Catholic pilgrims had arrived aboard the Ark and the Dove. Fulke eventually returned to England, but the remaining Brent siblings quickly settled into life in the colony, becoming active members of colonial society and government.

However, politics in the colony reflected those of the homeland, and so even though Maryland had been established as a place of religious freedom, it, too, suffered the anti-Catholic persecutions that were revived in England under King Charles I. As a prominent Catholic family, the Brents were easy targets in the colony. During the Richard Ingle Rebellion of 1645, in which the homes of Catholics were raided and ransacked, Giles Brent was arrested and sent back to England along with several other Maryland Catholics. Lord Baltimore’s government was overthrown, and the governor fled to Virginia for a time. Giles Brent eventually returned to Maryland, although he and his family moved to Virginia soon afterward.

His sisters, Mary and Margaret, were active members of Maryland society. Neither ever married, a fact that historian Lois Carr highlights: “Their single status was more unusual than perhaps most people realize because in coming to Maryland they moved to a society in which, at this time, men outnumbered women about six to one. The pressures on them to marry must have been extreme, unless they were protected by vows of celibacy” (Lois Green Carr, Margaret Brent – A Brief History, Maryland State Archives). Carr proposes that both Mary and Margaret may have been members of the Institute of Mary religious congregation founded by Venerable Mary Ward in 1630. Women in Ward’s community took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, but they lived in the world and did not wear religious habits – a very unusual form of religious life for women in the 17th century. Although the community was supported by Pope Urban VIII, it was viewed with suspicion by many Church contemporaries, and detractors referred to Ward’s community as “Jesuitesses.” Whether or not Margaret and Mary Brent belonged to this community remains conjecture. What is certain, however, is that their single status in Maryland and later in Virginia allowed them to maintain proprietorship over their lands and goods, affording them a privileged position in colonial society.

Margaret’s own status and talents were such that she was chosen by her cousin, Leonard Calvert, to be the executor of his will – a remarkable position for a woman at the time. In carrying out her role as executor, Margaret made the bold move of petitioning the Maryland colonial government for two votes: one for herself as a landholder, and another as Lord Baltimore’s legal representative. The votes were denied her, but she did gain a seat in the government, making her “the first woman legislator in the nation’s history” (Gerald Fogarty, Commonwealth Catholicism, 2001, p 14).